Home » Articles posted by Poe M. Allphin

Author Archives: Poe M. Allphin

Grief! in the Archive

I started really exploring archives in 2021 — which meant that until recently, most of my archival experiences were digital. Digital archives and digitized archival materials are imperative resources in making research and history more accessible, and the Digital Transgender Archive and JSTOR’s Independent Voices collection have allowed me to familiarize myself with many independent publications and make intergenerational trans connections. Even so, the physical and digital archive experiences are different — different in a way that I have found to be emotionally intense. In person, the experience was often more like sorting through a loved one’s things after their death than the CTRL + F mechanism that dominated my digital archive surfing.The viscerality of holding Adam O’Connor’s last journal and seeing how many pages went unfilled would be hard to reproduce digitally — would a scan even include the empty pages, or just the ones he had time to fill?

Image description: a white person’s hand holds open a graph paper lined notebook. There are a few illegible marks in black ink on the left page and the right page is empty. The hand shows the amount of the journal, maybe a third to half of it, that was left unfilled. A blue-gray archive box and yellow folders are visible in the background.

Another in-person contrast to my digital archival experience is the ways in which the materials are organized, or rather, my interactions with how the materials are organized. The chronology gives me a sense of first time traveling backwards forty-odd years, then forward again one year at a time. In encountering the organization files of the New York City Gay Men’s Chorus (NYCGMC) at the NYPL, for instance, I found a folder for each year. At the Lesbian Herstory Archives, I came upon a chairman’s note in an NYCGMC December 1980 concert program that referenced “the November 19th tragedy,” which I later found referred to the Ramrod Bar shooting during which former NYC Transit Authority cop Ronald K. Crumpley killed Vernon Kroening and Jorg Wenz at a Greenwich Village gay leather bar. As 1981 dawns in the papers I rifle through, I feel a sense of increasing dread, even guilt, as I know what’s coming even though my subjects do not. AIDS. I feel simultaneously omniscient and powerless.

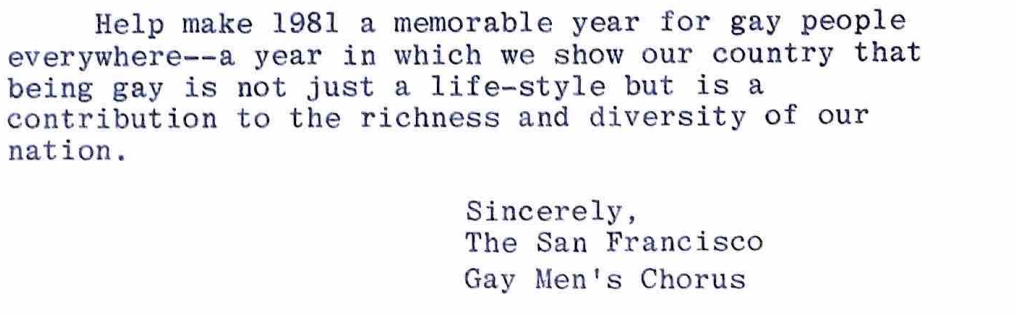

Writing in early 1981, the San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus urges prospective donors for their upcoming national tour to “Help make 1981 a memorable year for gay people everywhere.”

Image description: slightly faded serif printed text reads “Help make 1981 a memorable year for gay people everywhere – a year in which we show our country that being gay is not just a life-style but is a contribution to the richness and diversity of our nation. Sincerely, The San Francisco Gay Men’s Chorus.”

One of the aspects of going through a personal collection that can make it feel odd is that you are going through someone’s stuff — even if they donated it, even if they’re dead. It can seem voyeuristic, one-sided. In a way, reading someone’s memos, their notes on the back of a weekly chorus bulletin, even their diaries — although arguably one-sided, this is a more intimate knowing than I have with most acquaintances and even many friends. The one-sidedness makes me wonder if maybe it’s like mourning the death of a celebrity you never met in person — but no, it’s much more intimate than that. You’ve held things they held and read their private correspondence, maybe even their diaries.

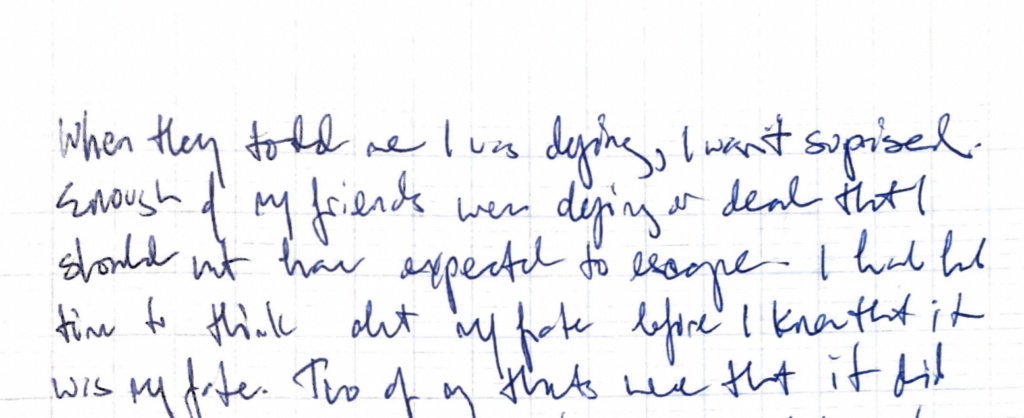

There are instructions on how to handle the materials in a physical sense — keep the folders flat on the table, remove one at a time — but no one prepares you for how to handle what you find in the folders. Folders full of memorial service programs, diary entries reflecting on one’s own mortality or listing sick friends.

Archival grief to me is mourning the loss of someone you never met but feel as if you’ve gotten to know.

Image description: blue ink on graph paper reads “When they told me I was dying, I wasn’t surprised. Enough of my friends were dying or dead that I shouldn’t have expected to escape. I had had time to think about my fate before I knew that it was my fate.”

Perhaps my grieving for these people I never met is my way of trying to bridge the gap, of making the archival experience a bit more two-sided.

(In the past few years, work such as that by Lynette Russell, Cheryl Regehr et al., and Jennifer Douglas et al. has begun to discuss affect in the archive and archival grief responses, but it remains a newer topic of focus.)